INTRODUCTION

Earlier on this blog, I posted a “simple” recipe for amaro. I’ll admit that while it spelled out steps in simple terms, it wasn’t the most basic how-to recipe. What follows is a recipe and method that will have you creating a delicious, accessible and appealing amaro that you can imagine and it will be sought after by all those who sample it. The only real difficulty is a few algebraic calculations in setting your concentrations.

This recipe was originally designed to mimic Amaro Nonino – an amaro that is both complex and extremely versatile in its appeal and application. Amaro Nonino is one of the more expensive amari on the shelf, and it’s understandable. While it has some wonderful and easily identifiable orange notes, they are accompanied by so many other subtle flavors that it stands out as one of the best amari for introducing one to the world of Italian bitters and herbal concoctions. Fernet Branca is a favorite among bitters enthusiasts because of its unique and strong minty notes, but Nonino brings the whole experience up to the front door of palate exploration for the initiate. From Nonino, you will want to sample the warm familiar flavors of Cio Ciaro, Meletti, Averna and Amaro Montanegro. When you’ve tired of the familiar, you will venture out and seek the intensity and immersive experience of Fernet Branca or maybe another intense herbal flavor like the French liqueur Chartreuse.

As I started laying out the ingredients and steps, it dawned on me that there is no set recipe here. I can’t to do that to you because there are too many delicious variations to ignore and you may desire something completely different. Thus, what follows will not necessarily mimic Amaro Nonino. If Nonino is your desire and you do want to try and make this Amaro Valencia as the title implies, I’ve flagged the ingredients used with a double asterisk **. Ultimately, your taste will dictate the final results (of course!).

The timing is the most frustrating part of making amaro – you have to wait! The recipe that follows will have an immature, but tasty amaro (nearly a gallon’s worth) in about 4 weeks. The longer it mellows, the better the final result. This will create an amaro that is right around 60 proof (30% ABV). If you want something that warms the stomach as well as the palate, you can boost it to 35% or, if really adventurous, 40%. One note, however: a higher concentration of alcohol will result in slightly reduced yield of finished amaro per these starting quantities.

Let’s get started, shall we? I will begin much like a painter, and build a palate of flavors. First, we’ll assemble our supplies. Here’s what you’ll need:

SUPPLIES

- A 2.5 liter “growler” or a gallon jug with a lid.

- Several 4oz. tincture bottles– most herbal supply shops sell these. You are going to be creating some tinctures and these are perfect for storing them. Some come with small lids, others come with droppers. I like the ones with droppers for the stronger flavors.

- Coffee strainer with paper filters

- Some funnels of varying sizes.

- 3 – 6 feet of Aquarium air pump tubing for siphoning liquid

- Mason jars – these are for mixing quantities larger than what the small tincture bottles can hold.

Next we’ll assemble our ingredients…

INGREDIENTS

- 750ml up to 2 liters of a neutral spirit at 75% ABV (alcohol by volume) or 151 proof. I strongly recommend Everclear Grain Alcohol (ethanol). If you cannot get Everclear, substitute a clean vodka at 40%ABV (or higher if available). If you’re able to get 95% Everclear (190 proof), that’s great because it’s the most economical. We will still want to add enough distilled water to dilute it to 75% ABV.

- 1 gallon of distilled water – or filtered tap water – as flavorless as possible.

- Dried herbs and roots. Get at least one ounce (by weight) of the following:

- Allspice berries

- **Angelica root (chopped or shredded) – bittering agent

- **Anise (star anise is very intense and available from the grocery store) or Fennel seed

- Cloves

- Cinnamon sticks

- **Centaury

- Coriander seed (crushed)

- **Cardamom seeds (crushed)

- Cinchona Bark (extremely bitter – use with care!)

- **Gentian root – check a local botanical store or any number of online stores. This is a foundation for amaro and the most basic bittering component.

- **Galangal root (found in any place that sells ingredients for Asian or Indian food)

- **Juniper berries

- Lemon peel (take the peel from a lemon and slice it in such a way as to remove the white pith from the yellow peel (about 2mm thick). Take this and dry it on a baking sheet in the oven at 200 deg F for about 1-2 hours. The peel should curl and feel fairly hard once it’s dried.

- Lavender

- **Valencia orange peel – prepare as above for lemon peel. If you can get truly organic fruit, these are the best and have great flavor.

- Orris root – a strong bittering agent

- Fresh herbs (if possible)

- Peppermint

- **Rosemary

- **Sage

- **Saffron

- Wintergreen – fresh leaves only, or Wintergreen oil

- **Wormwood (another bittering agent – find fresh leaves if possible)

- **Vanilla bean

You can also add some of these more exotic and less available herbs…

- Balm of Gilead

- **Hyssop

- Sassafras

- **Lemon balm (Melissa officinalis)

- Myrrh resin

** Used in Amaro Valencia

Then you will want some of these finishing ingredients…

- Oak chips (medium or dark toast)

- Raisins (dark or golden – I use dark for their color)

- Sugar, or for a slightly less sweet but milder flavor, honey.

- Glycerin (optional – used to thicken a liqueur to give it a heavy mouthfeel) – be sure to purchase food grade!

- Bentonite – a powdered clay for pulling out oils and other clouding agents in liqueur (and wine). You can find this at any homebrew supply shop.

- One egg white – used in conjunction with bentonite to pull impurities out of your mixure.

PREPARATION

Tinctures – prep/finishing time: 2-3 weeks

Begin making tinctures. Take 1 teaspoon of each desired dried herb and place it in the tincture bottle. Fill the bottle to the neck with 75% alcohol.

For berries and clove, add one tablespoon of these in the tincture bottle and fill to the neck with 75% alcohol.

For lemon peel and orange peel, make sure the peel is dried and then place about 1-2 tablespoons in the tincture bottle and fill with 75% alcohol or 40% vodka. The lower spirit tends to extract flavors a little more faithfully.

For all other ingredients (star anise, cinnamon bark, vanilla bean) usually one to two of each in a tincture bottle are sufficient. Fill with 75% alcohol.

Tinctures will begin to develop their character after 2 weeks.

IMPORTANT NOTE: For fresh green herbs such as Sage, Rosemary, Peppermint, etc. : Remove the leaves from the tincture after 4 to 5 days. The tinctures will turn a beautiful deep green color that quickly turns a dusty brown if the leaves remain in alcohol too long. The flavor doesn’t degrade as much as the color, but having a tincture that remains a clean color seems more palatable in the final flavorings.

Base Spirit – prep time: 1 week

Bitter

Fill a mason jar with 1 cup (8 oz.) of 75% alcohol. Add 1 tablespoon (each) of your desired bittering agent(s) – with the exception of orris root – add only ½ teaspoon or omit it completely. I recommend using gentian (always), angelica and wormwood. Cap the jar and store it in a dark cupboard for 4 to 7 days.

Faux Brandy

Take a second mason jar and add ½ cup of raisins. To this add 1 cup of 75% alcohol. Cap the jar and store in a dark cupboard for 4 to 7 days.

Finishing agents

Simple Syrup

Simple syrup is made by dissolving 2 parts of granulated sugar into 1 part of clean water (distilled, or filtered water is best) in a saucepan over heat. Heat the water until the resulting solution is perfectly clear. Allow the syrup to cool to room temperature before pouring it into a bottle or other container.

Caramel coloring – use caution!

Caramel coloring is created by heating granulated sugar until it caramelizes, turns dark reddish brown and then adding boiling water to the resulting liquid to dilute it enough to be pourable. This is the only process in the making of amaro that requires a little bit of care. The caramelized sugar can produce a fair amount of smoke that might set off a kitchen smoke alarm, and if left on its own for a few moments, might create a hard tacky sludge that will stick to and ruin any cooking surface (including the saucepan).

- Place a pot or kettle of water to boil. When the water is boiling or near boiling…

- Take 1 cup of sugar and heat it in a saucepan over medium high heat.

The sugar will begin to liquefy and brown. Tilt the saucepan to keep the liquid together rather than letting it spread over the entire saucepan’s surface where it could boil dry.

- As the liquid browns, keep stirring to prevent it from sticking and burning. Keep stirring the sugar over heat until its color becomes a very dark brown, almost black. When it is sufficiently dark (and still liquid!), turn off the heat. Proceed to the next step quickly.

- Using a pot holder or other hand protection, CAREFULLY pour about ¼ cup of boiling water into the sugar liquid. It will violently steam, bubble and foam briefly. Begin stirring as soon as possible so that the viscous sugar liquid is even diluted with the water. Allow it to cool to room temperature and then pour it into a tincture bottle or other small container.

The more caramel coloring you can create, the darker your amaro can become.

Oak barrel aging or toasted oak chips.

One can get a 2-5 liter oak barrel for $75 up to $200. These allow your liqueur to age and develop smoothness and take on additional complex flavors that result in a truly special end result.

You can also purchase oak chips from a homebrew supply store for anywhere from $4 to $20 depending on the variety of oak, darkness of the toast, and quantity. I like using oak chips because they’re more economical and they impart the magic of toasted oak more quickly than barrel aging. The tradeoff is the quality of the oak flavors. Because a barrel breathes, tannins and other qualities are constantly being exchanged through the barrel walls with the liqueur, creating flavors that are more complex than what you get with oak chips.

Preparing oak chips (can be done in advance)

To prepare oak chips, take 2-3 tablespoons of toasted oak chips and cover them with a cup of water in a medium sized saucepan. Heat the water until boiling and then reduce the heat to a light boil (medium heat). Allow this mixture to simmer/boil for up to 1 hour, adding more water if necessary, until the water turns to a nice toasty brown color. Typically, you might end up with ¼ – ½ cup of liquid with oak chips. Double this liquid with alcohol at 40% – 80% and store in a cool dark place to age (at least one week).

Putting everything together

You should now have:

- several bottles of tinctures;

- 1 cup (8 oz.) of bitter alcohol containing your bittering agents;

- 1 cup (8 oz.) of faux brandy (raisin mixture)

- ½ cup of dark oak liqueur

- 2 cups (nearly) of simple syrup

- ¼ – ½ cup of caramel coloring

At this stage I would recommend having additional neutral spirit on hand to help adjust and expand your liqueur to the desired quantities and dilution.

- Pour the bitter alcohol and faux brandy through a coffee filter into your growler or gallon bottle. Pour each mixture separately so that you can keep the remaining solids in the mason jars separate. We’re not ready to dispose of them yet!

- Now, we want to sweeten our base, but we want to carefully control the alcohol concentration. If you add simple syrup by itself, you run the risk of diluting your base too soon, possibly constraining your ability to further craft the flavors. To get around that, we add alcohol to our simple syrup to make a mixture that’s both sweet, but also comes close to the desired alcohol content of our finished amaro. The formula for this is:

Where…

v = starting volume of non-alcoholic liquid (simple syrup)

n = amount of neutral spirit to add

e = current volume of ethanol (in the original solution) <–this is for increasing an existing concentration

%n = alcohol concentration (%ABV) of the neutral spirit

d% = desired alcohol concentration (%ABV) of finished mixture(n x %n) + e = (v + n) x d%

Let’s say that you have:

- v = 2 cups (16 oz.) of simple syrup

- n = some amount of neutral spirit to add (what we’re computing)

- n% = 0.75 ABV (the percentage of neutral spirit we’re adding)

- d% = 30% ABV desired amaro concentration or 0.3:

Since our simple syrup contains no ethanol, we use zero 0 for e

0.75n + 0 = (16 oz. + n) x 0.3

0.75n = 4.8 + 0.3n

0.45n = 4.8

n = 10.6 oz. of neutral spirit to add, or roughly 3:2, i.e., 3 parts syrup to 2 parts alcohol

- Begin slowly adding your sugar/alcohol mixture to the base in the gallon bottle. Start with ½ – 1 cup, but keep track! You’re going to know exactly how much you’ve added in order to compute your amaro concentration later.

NOTE: Sugar is NOT soluble in alcohol. It needs water to stay in solution. If you add too much alcohol to your simple syrup and reduce the ratio of water too much, the sugar will begin to precipitate out of solution and form crystals at the bottom of your container. It isn’t that big a deal, but if you store this simple syrup/alcohol mixture for a length of time without using it up, sugar will most likely begin crystallizing at the bottom. It won’t be useful for sweetening other batches.

If your palate is immune to high alcoholic concentrations, you can take a teaspoon and sample the liqueur for sweetness. If you’re like me, that’s just a little too harsh to taste. Take 1/2 oz. of the mixture and add another 1/2 oz. of distilled water and taste it. Is it sweet enough? It’s going to have a kick because of the bitters and the alcohol, but if it goes down without a grimace, it’s probably pretty good.

If you added a whole cup of sweetener, your alcohol concentration is now:

16oz. @75% + 8oz. @30%

= (16 x 0.75) + (8 x 0.3)

16 + 8

= 14.4 / 24

= 0.6 or 60% ABV

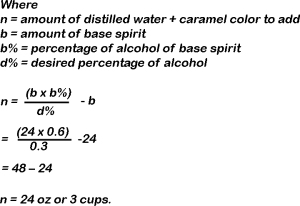

- Add enough distilled water to your caramel coloring to dilute your base spirit to the desired concentration.

- Sample your base spirit. Is it still sweet enough? If not, add enough of the alcohol syrup mixture to satisfy your palate. Err on the less sweet for the time being. Keep track of what is added so that you know the total liquid volume!!

- Now, create your masterpiece! Begin by adding 1/4 – 1/2 oz. of the tinctures to your base spirit. I recommend the following order so that your palate doesn’t become too confused:

The bitter is done. Now, create and craft the herbal flavors!

Note!: Some flavors quickly overpower any other herb and should be added in small amounts. The strongest of these is cinnamon and cloves. Leave them out until the very end and add them only if your resulting flavor is too dull. The next strongest flavors are anise and peppermint. Anise will also overpower your mixture, but it will mellow a little with the addition of other flavors.

- Orange peel

- Juniper

- Sage

- Centaury

- Coriander

- Cardamom

- Rosemary

- Allspice – be careful and add a little less

- Saffron

- Vanilla

- Lavender

- Galangal root

- Anise – be careful, here!

Once you’ve added anise, mix the flavors and sample the result. Remember, this is not going to taste much like an amaro yet, because the flavors are too raw. But you want to get an idea of its complexity.

Here you can experiment with all of your tinctures and add them bit by bit until you taste their contribution. To pull your flavor profile out of the extreme column, adding more orange peel and vanilla often ease it back. Galangal is an interesting flavor because it hides behind other flavors and amplifies them a bit.

If you want some sharpness to your amaro, add peppermint. If you want it to be spicy, add the cinnamon – but carefully! Cinnamon is a rare instance of an ingredient that adds much more heat than flavor. You might have a hard time discerning cinnamon in your mixture, but you will most certainly feel it! I often leave cinnamon out of the party because I have a hard time pulling it back if it’s too strong.

A little bit of clove goes a long way and will also mask other more subtle flavors. Add clove if your amaro isn’t exotic enough, but just take it slow!

Keep adding dashes of tincture until you have your desired flavor.

- Sweetness – revisited. Now that you’ve crafted your flavor, you can readjust the sweetness if so desired. Just add the simple syrup and alcohol mixture at the same concentration to maintain your desired sweetness.

- The finishing touches

- More oak? Once you have created a flavor profile that you find promising, it’s time to put the mellow in. Take your oak liquid and slowly add it to the mixture (about 2 oz. at a time). Taste the result. Can you taste the oak? Can you taste the additional warm vanilla notes that the oak leaves behind? Can you taste the old wood paneled boardroom? No? Add another 2 oz. and taste again. When you get a hint of oak, stop there.

Well, what do you think? You’re probably getting pretty psyched about what you’re tasting. If you think your amaro is still too harsh, or doesn’t have that je ne sais quoi, you can take some additional toasted oak chips (no more than 1 teaspoon!) and float them in the bottle. They will take between 1 and 2 weeks to really have an effect. When the time is up, remove the oak chips.

- Sweetness? At this stage you want to make sure that you’ve gotten the sweetness to the desired level. Add your simple syrup mixture to adjust. Also, at this stage you can extend your amaro by adding a little water and alcohol to give a desired volume. Just make sure to keep your concentration consistent.

Color and clarity – make it look amazing!

Once your amaro is nice and mellow and seems like it’s coming along, let’s examine its clarity. Is it cloudy? Are there little gossamer threads floating around in there? Does it look like dust motes floating in sunbeams? If so, it’s time to get that stuff out of there!

- Fining your amaro – Bentonite and egg white:

Pour 1 cup of boiling water into a mason jar and add 1 teaspoon of bentonite clay powder. Using a pot holder, shake this mixture up until it becomes a cloudy gray and the bentonite powder dissolves. (It won’t completely dissolve, but you don’t want to see dry powder sitting in the bottom of the jar). Leave this overnight to cool and dissolve.

The next day, shake your bentonite well to distribute the clay evenly. Add about 2 oz. per gallon of amaro. To this, crack a fresh egg and add only the white to your amaro. Cap the amaro bottle and shake it vigorously. You want to distribute the egg white and bentonite throughout the mixture. Once it’s thoroughly mixed, set your bottle back in the cupboard. And wait.

Within the hour, you should start to see a sludge forming in the bottom of the bottle and very clear, transparent liquid sitting on top. Allow this settling process to continue throughout the day.

- Racking

When it seems that you have a nice clear liquid floating on top, insert some air tubing into the upper portion of the bottle and secure it with a binder clip or clothespin on the lip of the bottle. Start the siphon and siphon off the clear liquid into another gallon bottle or several clean mason jars. If you have an oral syringe, you can attach that to your tubing to get your siphon started (or you can use the tasty old-fashioned method). Siphon as much of the clear liquid as possible. This is termed “racking” the mixture.

- Filter

Once you’ve pulled as much clear liquid as you can, set it aside. Put a coffee cone and filter on a clean mason jar. Pour the sludge and impurities into the filter and allow it to drain into your mason jar. You may have to change coffee filters several times as the sludge stops the flow completely. NOTE: This secondary filtering of the sludge can take hours to complete. When you have poured all of the sludge through filters, you should be left with some beautifully clear liqueur in your mason jar.

Take the mason jars of the liquid that was racked and pour them through a coffee filter. Note: sometimes the filter is more effective if it already has a thin layer of impurities at the bottom. It helps close up the pores of the coffee filter. Once you’ve filtered all of your liqueur at least once, transfer it all back to a clean gallon bottle.

You’re done!!! You now have a gallon of amaro that can be bottled into 9-10 ea. 375ml bottles, or 4 ea. 750ml bottles. Or, you can let your gallon bottle sit for a week or two, making sure that any other impurities will settle out of solution. Rack the bottle one last time.

Micromanaging – that’s right. You get to touch the stuff one more time! If your amaro isn’t dark enough, feel free to make additional caramel coloring and add that as desired.

Hi there, thanks for all of the great information- I was wondering about the steeping time for the herbs. In an earlier post, I think you had the time at 2-3 days instead of 2-3 weeks here… Am I mistaken? If not, why the big change? I’ve made 3 bottles loosely based on yours and other recipes and Ive gotten positive reviews. And most importantly since I am drinking it more than anyone, I love it.

Hi Jason,

Sorry for the confusion – the difference is that here I’m creating small 4 oz. bottles of tinctures – making sure that the essence of the herbs is fully developed and present in the alcohol. It’s a different method of flavoring than the earlier post. If you’re adding the herbs directly to your base neutral spirit as in the first recipe, you don’t want them creating flavors that are too intense and overpowering. Two to three days is usually sufficient. The tinctures are a little more forgiving because you can decide (once they’re created) how much of each flavor you want to add to your finished product – I’ve found it a much more controlled way of going about it. Either way works well if you’ve established your own recipe.

Does that make sense?

Thanks for the question.

Kurt

Absolutely, do you find that this allows some of the individual flavors to stand out more in the finished product, rather than a “mish mosh” of sorts?

Also I’ve been using fresh orange peel for bittering, how do you find drying them out in the oven changes the taste?

Hey Jason,

Tinctures – Exactly. I have about 25 tinctures, from anise to sage that I use to flavor my amari precisely. What it lacks in a repeatable method (you certainly wouldn’t mass-produce an amaro this way) it makes up for by being amazing every time. If I use too much of one flavor and it’s overpowering, I can always compensate with the tinctures.

In my experience, with the exception of green leaves or plant stems, most herbs and components like orange peel take on a smoother, more mellow-in-the-mix character if they’re dried. Orange peel, for example, is much more citrusy and pungent if fresh. It changes with more sweetness and bitterness (and a sweeter fragrance) when dried.

But, as I’ve said throughout my posts and comments, if it works for you, go with it! Why not try it both ways and see which you prefer?

Thanks again for the comment.

I’m thinking about trying the tincture method- how long would you say they last, do they lose their flavor over time?

Yes, unfortunately, they do lose their flavor – over time, any leaf-based tinctures(wormwood, hyssop, lemon balm, etc.) all begin to take on a non-descript dull vegetal flavor – like an overcooked artichoke. Not really disgusting, but not very appealing either. Other tinctures like anise and orange peel still taste like themselves, but with a much lower intensity.

I’ve found tinctures that last as long as a year, but most of them seem to lose their flavor after about 3-4 months. It they’re at the peak of their flavor, you’ll find that just a 50ml eyedropper of one imparts a noticeable flavor to whatever you’re making. After 6 months or so, you need about 1 ounce or more to affect the same change in flavor.

I am trying this for the first time and was considering adding glycerine since I do love that round mouth feel. Can you tell me a bit more about that? How much do you add? Will it alter the flavor at all? When do you add it? Any words of caution? Thank you for such a detailed recipe!

Hi Claire,

Thanks for the question. Glycerin does make the amaro feel more syrupy and smooth, but if you use too much, it can have a very slight laxative effect (nothing too drastic, really). I don’t use it as often any more because it sometimes makes my amaro less crystal clear, but when I do, I would use no more than 1/4 cup to a gallon of finished liqueur. If you’re adding it to a bottle, I would use a maximum of 3 tablespoons. Go tablespoon by tablespoon until it works. Be sure you’re buying food or pharmaceutical grade (96% purity or greater).

Also, you want to make sure it is the last thing you add to your amaro. If you add additional water to dilute the concentration, your liqueur will get somewhat more cloudy (see above). I hope that answers your question.

Good luck!

Kurt

Greetings – great stuff, thanks for all the work and sharing. A few questions.

First, when you recommend proportions of herbs and spices to add to tinctures and to the base liquor, are you talking about ground or ‘cut’. I’m particularly concerned about cinchona here, but I’ve also got ground gentian and rhubarb root (my wormwood is cut not ground).

Also, what about the flowery end of things, any experience with rose petals (or rosewater)? Other flowers? Fresh fruit?

I’m also absolutely in love with Barolo Chinato, which of course has so many shared characteristics with amari’s bitter roots and herbs. Have you ever added wine, or used substantial amounts of wine instead of water to dilute your base liquor? (I did read your other posts that recommended using vermouth, which strikes me as a bit redundant with this process…I’m thinking of an amaro that has a similar flavor profile to a Chinato.

Thanks a bunch and keep it coming!

Hi Matt,

Thanks for commenting.

As far as tinctures are concerned, a little does go a long way. I usually use cut herbs, or if they’re ground, they’re done coarsely with a mortar and pestle. Cut wormwood is the way to go. As you know, cinchona is a very, very strong bitter bark. It’s similar to cinnamon in terms of its strength. I would add no more than a 1/4 teaspoon to 4oz. of alcohol. After that, I would use that tincture extremely sparingly. It will easily overpower your recipe with an astringent bitterness if you’re not careful.

Flowery ingredients are nice, though I would recommend drying them before using. You lose the volatile flavors that way, but they leave over time in solution anyway. I think it’s best to have a flavor profile that more closely matches what will be experienced in the bottle.

As for adding wine to an amaro recipe, the answer is yes, I have. It definitely changed the character of the amaro – which might be good or bad. Wine (or vermouth) adds considerable brightness to a recipe, but it also adds some tartness – which I find a little out of place in an amaro. But you can fool with the concentrations and use it as a polishing flavor – in very small amounts!

I’m a Ramazzotti fan, too. I haven’t had it in a while, so I can’t comment on its flavor components with any great accuracy right now – I think I did identify some characteristics in an earlier post: see Amaro Flavor Detective. I would say the two main components you’ll notice in Ramazzotti are orange peel and anise, but they’re definitely toned down with…vanilla? honey? Not quite sure, but it is a nice mellow flavor – almost like a buttery root beer.

Thanks again for commenting and let me know how your recipes are turning out.

PS – I’m also a huge ramazzotti fan and have a number of lists of key flavorings, but any insights you have would be appreciated

Thanks a bunch.

… but I think the cinchona piece was a distraction from the more general question of measurements of say cut vs finely ground gentian (I have the latter).

I’m also now the proud owner of a number of sizable bags of ingredients (juniper berries, wormwood, gentian, licorice root)…can/should I freeze the stuff I’m not going to use for a while???

Hi Matt … I have a couple of thoughts on your question of ground versus cut ingredients – ground ingredients (let’s call them herbs for brevity) impart their flavors much more quickly than cut herbs – provided they’re not too finely ground to where they float on top of the solvent. At the same time, ground herbs also give off their volatile flavors much more quickly when exposed to air, making them stale more quickly. I actually prefer cut herbs (with the exception of black walnut since its ability to color my liqueur is much more effective when finely ground), because they do keep their flavors longer. I still do use a lot of ground herbs, though – galangal root, for one. It’s just easier to find it. Ground gentian root ought to work well.

Another reason I prefer cut is that you can control the types of flavors you want to extract from the herb. For example, I may not want the bitterness of cinnamon, but only the spiciness. If I use ground cinnamon – I’ll get both because all of the flavor oils and components are readily intimate with the solvent. Using cinnamon sticks allows me to pull them out of the solution when the spicy, flowery flavors have been transferred but before the bitter components are.

Lastly, I would not recommend storing your herbs and roots in the freezer. Unless you’ve manage to seal them up without any air, they’re either going to get freezer burned (dehydrated), or the opposite will happen when you do remove them from the freezer – moisture from the air will condense and give them a freezer flavor. It is probably not noticeable in the flavor of your liqueur, but you would know that some of the flavor has been compromised.

I keep my herbs in small apothecary jars, which you can order online. I find that my herbal ingredients cost about $20 total for a year’s worth, so if I have any left over after a year, I usually toss them and buy new. Some herbs are harder to get than others, so I might hang on to those.

I hope this helps!

Kurt

Hey! Finishing up my batch and I notice that my batch isn’t close to a gallon of amaro…how do I get it to be a gallon with sacrificing the flavor?

Hi Victor,

How short are you from a gallon? I usually find that my amaro is still very flavorable when I have to make up differences in volume. The interesting thing about neutral spirits is that by themselves, they don’t really dilute flavors that much.

My suggestion would be to mix up some neutral spirit and water to the alcohol concentration that you want your finished amaro to have (cut back on the water so you can add more simple syrup if you want) and add it. Before you do that, take a sample of what you have now, make up the desired volume and then take a sample from that. If the flavor seems really muted, dry the peel from an additional orange and let it sit in your finished liqueur for another week. I’m guessing you probably won’t need to.

I hope that helps. Good luck!

Kurt

Oh ok thanks. I’m not even at a half gallon though…

I’m just adding up the volume of liquid before “extending” it, and I get about 48-60 oz, which is about half a gallon. Do you really double the volume when you extend?

Hi Josh, it depends on your desired alcohol concentration. If you’re starting out with 95% Everclear, you’re going to dilute it about 2 times to get 30%. Adding a large volume of liquid might seem excessive, but the math doesn’t lie.

First, find the amount of alcohol you’re starting with:

1 qt (32 oz) of 95% Everclear contains 30.4 oz of alcohol. (32 X 0.95 = 30.4)

Next, divide that by the desired concentration (30%, as an example):

30.4 / 0.30 = 101.3 oz. total volume.

Now, find the difference between the total volume and what you have. Since you’re working with 32 oz already, subtract that from 101.33 and you’re left with 69.3 oz. that you need to add. That’s a little more than twice what you started with!

48-60 oz. sounds like a lot, but depending on your starting volume, it may be just right.

I hope that helps…

Kurt

Thank you, Kurt.

Hey Kurt,

Just to make sure I have this right. Using the numbers from your examples above, (i.e., using two 8oz mason jars with 75% abv 151 proof), you end up with 48oz at 30% abv. So are you suggesting, you could start out with larger amounts at the beginning, like 16oz mason jars instead of 8oz? Or are you suggesting, once you end up with 48oz at 30% you can extend that by just adding a 30% water/alcohol mixture? Thanks again.

Sorry to reply so late…You’re correct with either way. The main thing to remember is that you can always take a 30% mixture of water/alcohol/syrup and extend as much as you want – at least until the herbal flavors begin to weaken. That’s up to your nose and taste buds.

Hello, Kurt. First off, thank you so much for this. I love the thoroughness.

A question: Do you see any advantage to steeping everything together, perhaps adding ingredients at intervals so that none steeps too long? I know it’s a less precise and riskier way to proceed (also lazier), but I’m wondering whether letting everything stew in one jar might foster interesting interactions that cannot occur with tinctures. In cooking, preparing individual components of a dish and then combining them at the cooking, preparing individual components of a dish and then combining them at the end allows each part to retain more of its basic character and results in a cleaner overall flavor, but one loses the complexity that results when everything cooks in one pot. Does this hold true for crafting amari as well?

Hi Sarah,

Thanks for the question. There is no doubt that flavors will interact differently when macerated together for varying durations as opposed to cleaner additions of tinctures towards the end of the process. I have added flavors all at once myself, and I’ve experienced both a serendipitous, amazing concoction and at other times, a bit of a harsh mess. There is actually one major advantage to adding everything all at once: if it turns out well, your results are repeatable. That’s no small challenge when you’ve created a good amaro.

My suggestion is that if you decide to macerate everything together, you might want to prepare one or two tinctures to doctor the results if they’re unsatisfactory.

Good luck and let us know how it turns out!

Thanks for replying, Kurt. I absolutely get the reasoning behind using tinctures–so much more control–but the drama of throwing things together and waiting, waiting, waiting to see if the result is palatable kind of appeals to me. (this will probably cease after my first failure). Still, having some tinctures ready to course-correct in the event of disappointment makes a lot of sense.

Why would macerating everything together produce more repeatable results than carefully adding specific amounts of tincture? As long as one kept careful notes, wouldn’t an amaro produced with tinctures be easy to duplicate?

And one more question (sorry to be a bore, but I’m all excited), what do you think of producing a base amaro, whether with tinctures or by macerating everything together and then straining, and then suspending whole lemons over the infused alcohol and tucking the jar away for several months, as in the older style of making limoncello? Unnecessarily complicated (if fun)?

For that matter, would there be any virtue in suspending everything over the alcohol rather than macerating? (This is it for today, I promise.)

Hi Sarah…duplicating an amaro by macerating everything together (with measured amounts) is more effective for a couple of reasons having to do with tinctures:

1) All tinctures aren’t created equal. Some herbs have an incredibly strong presence and that carries over in their tinctures. The ability to adjust the flavor of the final mixture isn’t a constant among your components.

For example, a teaspoon of cinnamon tincture can make an entire gallon of amaro more spicy than you’d like. A teaspoon of orange peel tincture in a gallon might not make a difference at all. So while you’re adjusting the flavors, you’re constantly adding more of this tincture and a little dash of that. If your note-keeping is up to snuff, then you can probably duplicate your successes. In my experience, I’m so focused on flavors that I’m adding one tincture to blend with the one before it and if it isn’t strong enough, I’m adding more. Tinctures are flying off the shelf and being added before my palate gets jaded. Taking notes might lessen my creative timing – but that’s me.

2) Tinctures have a shelf life and their potency and flavor change over time. If you were to create a new batch of tinctures for each attempt at amaro, then you’re probably on your way to having a repeatable method – but that’s a lot of effort and a lot of timing.

Also, macerating everything together is definitely easier and therefore less prone to cutting corners. However, if you truly enjoy the process, then “easier” may not be a concern. As for me, I like the challenge of changing one edition of my amaro from the one before it. So tinctures do work for me in that regard.

Base Amaro…YES!

Producing a base amaro is an excellent idea and one that I employ if I’m making two or more amari at a time. I start with a bitter base and then add some basic flavor similarities (orange, anise, vanilla). I then have a nice base from which I can add new flavors to make some amazing different amari. For example, I might use a tiny bit of peppermint to give one an interesting nose, and another might have more juniper and galangal to make it more herbal, etc. Having a base amaro is really a great way to go.

I just saw your last question – suspending everything over the alcohol in a cheesecloth bag works well with very oily components (like oranges, lemons or damp roots), but I don’t really know if it is effective for dried herbs. To be honest, I’ve never tried it with anything other than the oily components I just mentioned. I can’t say with any expertise that it won’t work. Give it a try and see what you think. And please let me know.

Thanks again for the questions!

Hello, Kurt. Sorry to bother you again (I bet you’re regretting that I ever found your blog), but I have a couple of questions re the oak chips: First, when you say “2-3 tablespoons,” about how much would that be in ounces/grams? And what are your thoughts on the relative virtues of American, French, and Hungarian oak? I see all three (and more) for sale. I’m not planning on buying any right away (I’m toasting some oak in my oven as I write this), but it would be good to know which you prefer if I ever do decide to pay for someone else to do my toasting for me.

Thanks!

Questions are always welcome, Sarah! Not to worry. A palmful of toasted oak chips should be about right. If you add more of the desired toast, it isn’t going to hurt anything.

As for the variety, it really doesn’t make that much of a difference – your amaro is going to overpower any subtle differences in the variety of oak. If you were creating wine or brewing beer, American vs. French vs. Hungarian might be more of a consideration. The most important aspect of oak is its toast. I usually prefer a medium toast – any darker and you’re going to get some very woody flavor notes. Any less and the result might not be mellow enough, but that’s ultimately up to you. In my experience, medium toasted oak mellows your liqueur with a nice smooth vanilla component.

I always buy my oak at a homebrew supply store – they have bags of the stuff (French and American) for about $8 for 4 oz. Actually, French is just a little bit more.

Or, you can toast your own oak chips in an oven as you’re doing, or even on a grill if you’re not using direct heat. I hope this answers your questions.

Thanks, Kurt! That was helpful. My compulsive nature twitches at the vagueness of “palmful,” but knowing that there’s leeway makes me feel better.

I don’t know if my oak chips reached the proper toast, but they smelled wonderful in the oven (1.25 hours at 350 Fahrenheit). And I’m glad to know I don’t have to fret about having a specific kind of oak. I used white oak meant for grilling and smoking, and I guess that’s okay.

Here’s a dumb question: is angelica root supposed to smell like fenugreek?

Me, again. Am I crazy, or do you not explain why you want us to hold on to the solids strained from the bitter base and the faux brandy?

I should enlist your services as an editor! No, I didn’t specify what to do with the raisin solids from the faux brandy – I was probably going to introduce the idea of taking your remnants from the alcohol maceration and steeping them in 2 cups of hot water like tea, which can be used to dilute your liqueur while not sacrificing its character – but I never got to that point. It probably goes without saying that it isn’t necessary to save your solids here and I’ll adjust the recipe accordingly.

As for angelica root smelling like fenugreek, I suppose it would depend on the freshness of either. It wouldn’t surprise me, though. Many of the fresh roots (dandelion, angelica, etc.) all have a slight sweet smell reminiscent of each other, with some having a more mellow finish than others. Of course, everyone’s nose and palate have different sensitivities and experiences. Use what seems appealing to you and the result will be unique and probably quite enticing.

Ha! I was a copy editor for many years.(And thanks for letting me know I don’t need to worry about those solids.)

Regarding the angelica root, I asked because the sack I recently purchased smelled so much like fenugreek that I wondered if there’d been a bagging error. I have to buy everything by mail, or I’d’ve bothered my friendly neighborhood herbalist about it instead of you.

Thanks again and as usual!

I’d like to try making my own Averna and I was wondering what your recommendations would be to start? I love amaros and the flavor profile of Averna is my favorite. My goal was to understand that and then use that understanding to start branching out. Can you give me any guesses of what you might think would be a good start for ingredients? (p.s. I’m also in Seattle)

Averna is a very thick syrupy amaro, with some very strong flavor notes. The first obvious choice would be a bitter root like gentian, angelica or burdock. Other clear flavor notes are vanilla, caramel, and toasted orange peel. I think I would start with those. When you’re ready to add sweetener, you might consider creating a dark simple syrup with both sugar and molasses and letting it brown more than usual.

Most amari (Averna included) contain some measure of anise or fennel seed. I would create a tincture of those and add it to your recipe towards the end of the process. It’s a pretty overpowering flavor. Beyond these ideas, I’d suggest experimenting with other herbal flavors that you think you recognize in its makeup.

Try taking a 1/2 shot of Averna, dilute it with water so that its color becomes somewhat lighter and taste it. See if you can identify some of the flavors that jump out from that weak mixture. Experiment with that too. Sometimes diluting amaro helps your palate identify the different herbal components. Good luck!

I have a question about the clarifying: I followed your instructions adding the Bentonite and egg white. After letting it sit, everything floated to the top, not the bottom. Have you ever come across this before? Did I do something wrong or is there something that may cause this? Have you ever used Sparkoloid to clarify?

Thanks! Great article by the way, super helpful!

Hi Matthew – Sorry for the late response. Did you shake your liqueur so that the egg whites and bentonite were thoroughly mixed into solution? Depending on the oil content of your mixture, the clarifying can take a while. The egg white will float on top sometimes, creating a slurry that looks like bits of custard. If you shook up or thoroughly mixed up the liquid, these floating bits can be ignored or skimmed off the top. The clarifying will still occur.

I almost resorted to using sparkoloid after some disappointing results with the bentonite, but I noticed it was a situation where there was too much miscible oil in solution. It ended up just taking longer.

I’m close to finishing my first Amaro based on this recipe, and I’m real excited. I was wondering how I can split this into two slightly (or significantly) different tasting ones. Has anyone tried changing the mixtures of tinctures and bitters to get two different flavors? Since this is my first Amaro, I don’t want to adventure too much, but I’m going to have close to 4 liters of this, so I might have 2 liters to true recipe flavor, and another two where I can change this, but I don’t know how to go about this, what ingredients to reduce or remove.

Great detailed article and I’m so eager to try this once it is ready.Another 10 days to go!!

You can change the recipe any way you want to. It depends on which flavors you want to add. You can change the recipe by adding different tinctures if you want, or if you have dried herbs or spices, you can add those to your mixture. Tinctures will dissolve in solution

better than straight herbs, but their effect on a finished batch will be a little muted.

Another method would be to put additional flavors into a 75% neutral spirit (or vodka), let those macerate for a few days, and add some of that to half of your batch. The important thing is to maintain your desired alcohol content by not adding too much additional liquid (you can figure that out using the math), and to sample the mixture to make sure its sweetness and flavor meets your goal.

I absolutely urge you to experiment with flavors that appeal to you. At this stage, there isn’t much harm you can do to your batch, and by changing the flavor profile, it becomes more of a reflection of your tastes.

Good luck!

Thanks for your response and encouragement Kurt. I agree with you on changing and experimenting with flavors.

I followed your recipe ditto except the omission of a few bitters and herbs that I could not find at the time. So Angelica, centaury, juniper berries, lavender, vanilla bean are missing.

Beyond these, I am thinking of preparing 4 batches of one liter each. First batch will be as per the recipe, and after checking the flavors, I will try and remove some tinctures from another batch, and maybe add some other herbs, and change the flavors.

Thanks again!